Before using more EC probes in the field and gathering data from different parts of the stream I tested them in a controlled environment in the lab.

Experiment 1:

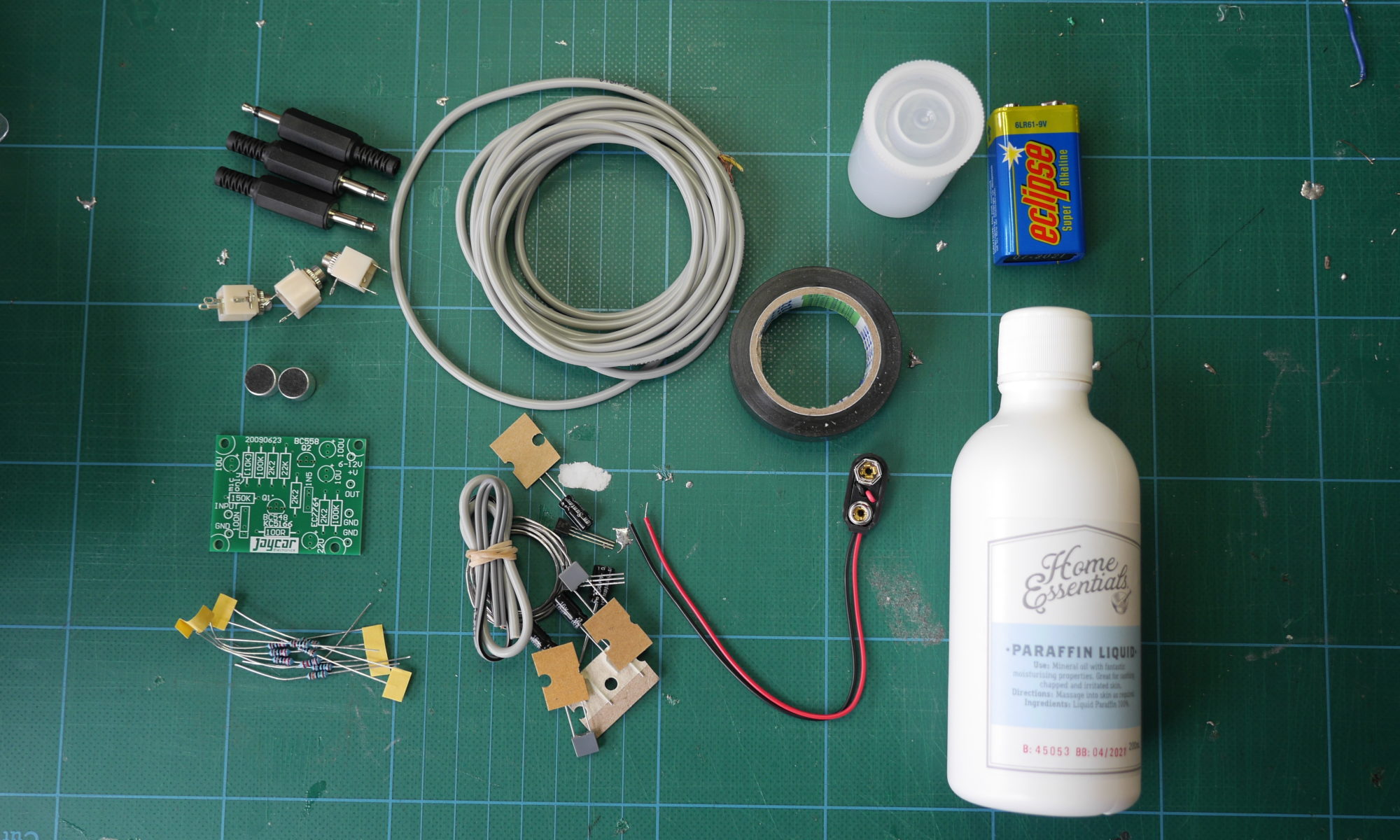

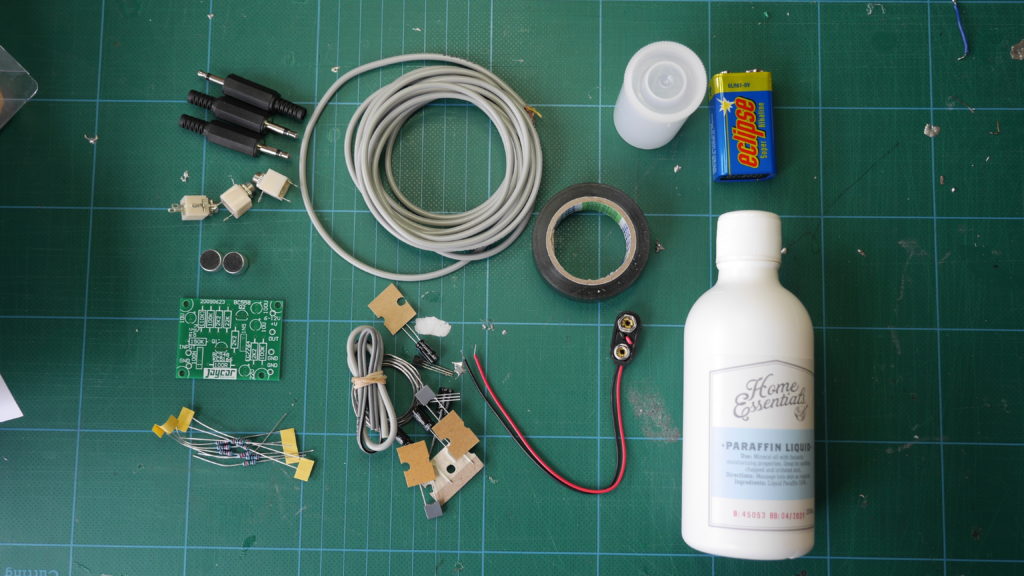

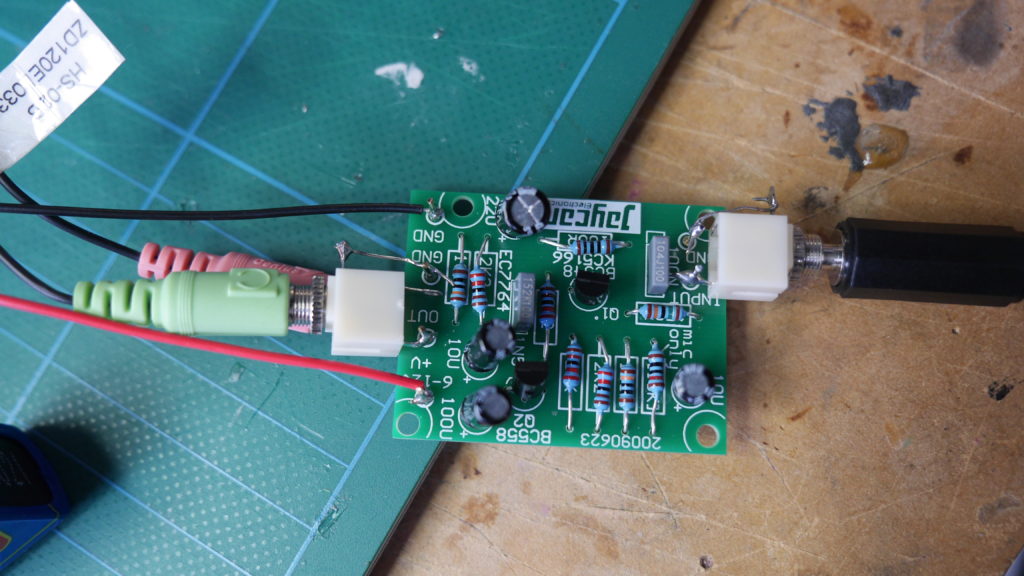

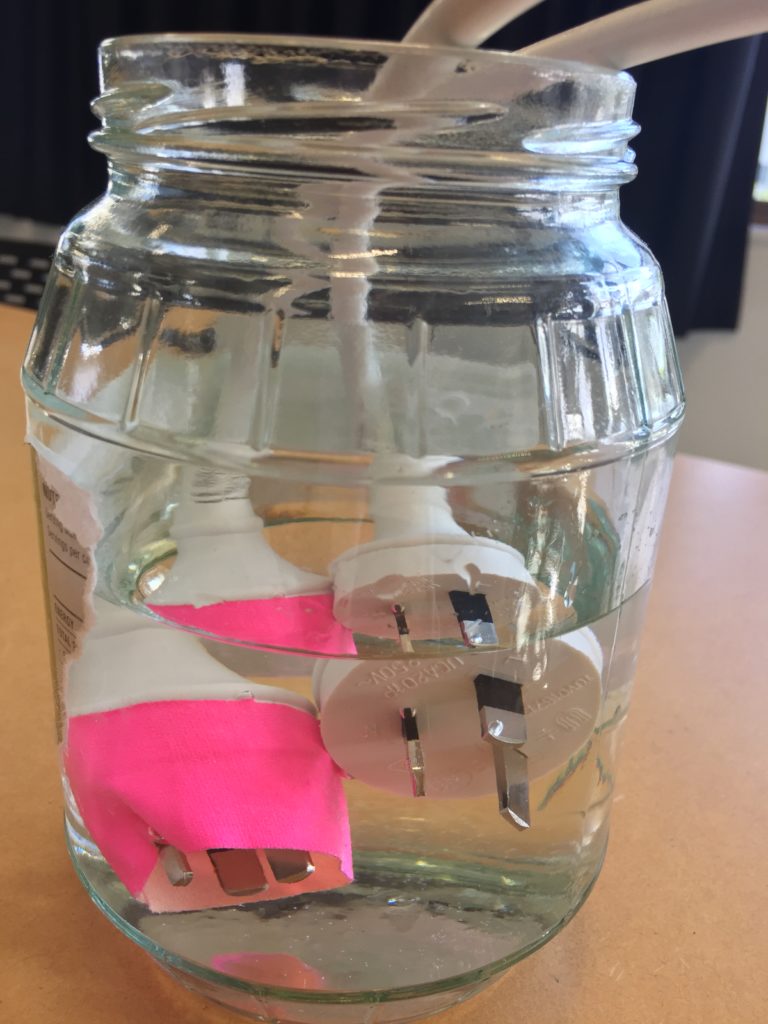

The two versions tested use the same materials, same length of chord and same 560 Ohm resistor. The first test involved a jar filled with tap water, immersing both sensors in the jar and monitoring the data via mosquitto_sub.

Note: The pink tape wrapped around one probe was an attempt to avoid the probe mistaken with a power plug on the lab table, which poses a severe hazard. The probes are stored away safely when unattended to ensure health and safety. This version of the probe uses the Live (L) and neutral (N) prong of the plug. To improve the safety of the probe the live (L) prong should be removed and Neutral (N) and Ground (⏚) should be used for measuring the electric conductivity.

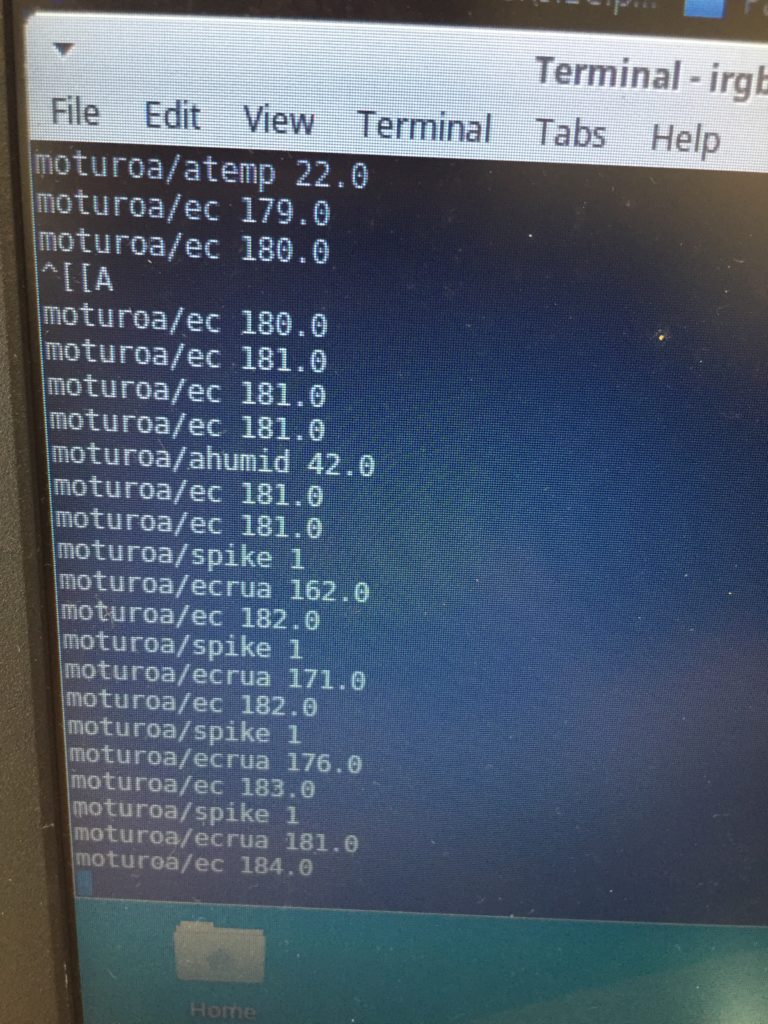

The terminal output shows the EC probes publishing the measured values under the topics motorola/ec and moturoa/ecrua. While the test recording was done, the DHT11 sensor was also active in the lab, publishing air temperature (moturoa/atemp) and air humidity (moturoa/ahumid).

This first test showed a deviation of around 10 between both probes, behaving relatively consistent. The next test would require measurements in the stream to see whether the probes return coherent readings from flowing water.

Experiment 2:

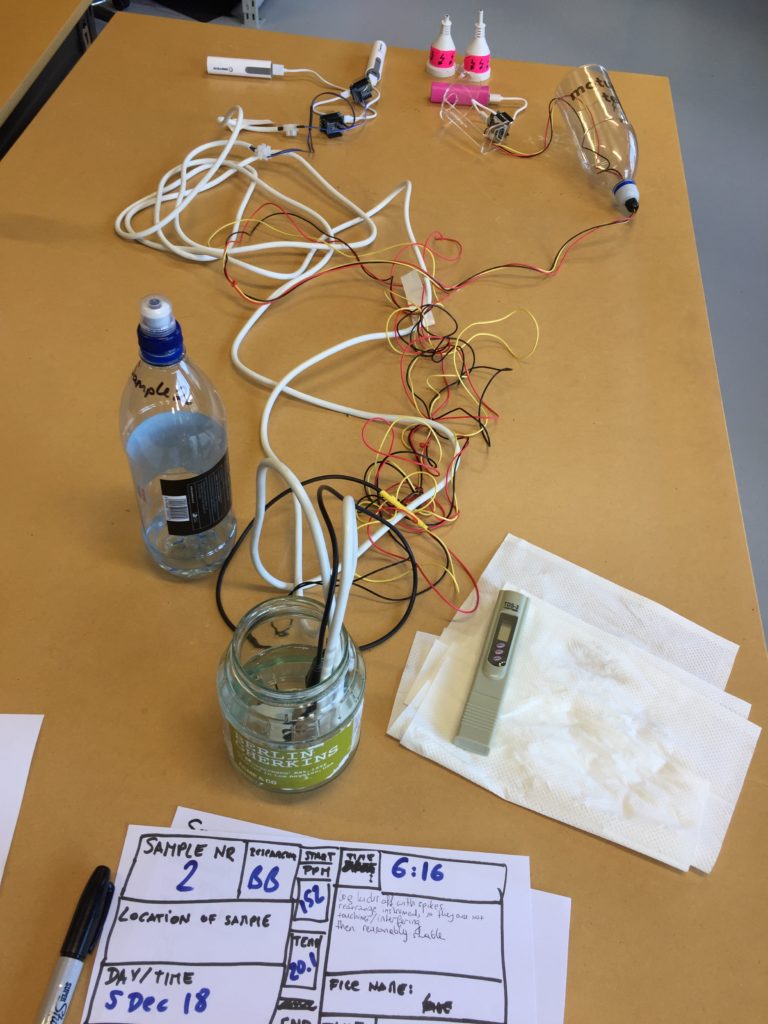

Due to bad weather and high winds it was too dangerous to conduct testing in the field. However, to get a better idea of the consistency between the two probes I went to an easily accessible part of the stream outside of the forested area and collected two samples of stream water.

Back in the lab I pour the first sample into a clean jar that is big enough to contain all three sensors. I prepared a paper sheet for keeping experiment notes, starting with date/time, location of sample taken, last weather and readings from the TDS meter at the beginning and end of the test.

- I boot the Raspberry Pi (the Pi acts as Wi-Fi Access POint hosting the Moturoa_Transmissions network and acts as the MQTT-broker).

- Connect laptop to Moturoa_Transmissions and start log with timestamp

mosquitto_sub -v -h 192.168.42.1 -p 1883 -t '#' | xargs -d$'\n' -L1 sh -c 'date "+%D %T $0"' > data.log

- Immerse probes into water sample and activate by connecting the Wemos D1 micro controllers to power supplies (USB batteries).

The raw data of both test results can be found on the development repository.